19 Princelet Street is one of the most extraordinary and – in recent decades – the most mysterious building in Spitalfields. Very few of the early-eighteenth century Huguenot houses of the area have not been restored since they served as sweatshops in the earlier twentieth century and overcrowded slums in the nineteenth century. Here however, the oppressive poverty of these people who inhabited its rooms most recently is still palpable. Most surprising is the survival of the Victorian synagogue built onto the back of the earlier house. Complete with its fittings and holy ark, it is a testament to a whole community which helped to define this part of East London but has since vanished with so little trace.

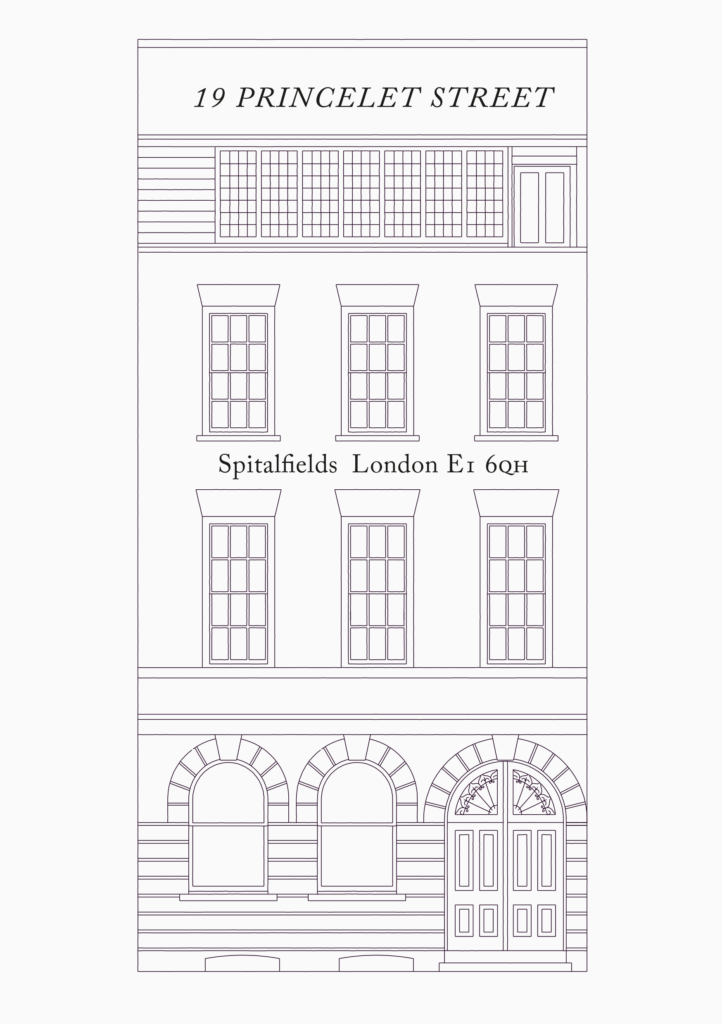

Number 19 Princelet Street is a five-storey Grade II* listed building in Spitalfields built in 1719 as a merchant house, and by 1740 documented as being occupied by the Huguenot Ogier family. Peter Abraham Ogier, the head of the family and a successful silk merchant and master weaver, had arrived as a seven-year old refugee in London in 1697. Towards the end of the 18th century a weavers’ garret was added to the house to produce silk fabrics.

In 1869 the building was purchased by a community of newly arrived Polish Jewish immigrants. In 1870 a synagogue within the house had been consecrated and by the early 1890s had been extended to occupy the rear garden with, below, a basement meeting hall for the synagogue’s ‘Loyal United Friends Friendly Society.’

The building functioned as a place of worship for this community for over a century, with a Hebrew school, and the basement put to many uses including weddings.

The top two floors were rented out to members of the community, including David Rodinsky who lived there with his mother and sister for some years then mysteriously disappeared in the 1960s, leaving behind a room filled with his belongings. By that time Jewish occupation in that area had diminished dramatically.

In 1980 the synagogue was deconsecrated then sold to the Spitalfields Trust. The Trust purchased the building with the original synagogue furniture and artefacts in situ, along with all the contents of Rodinsky’s room. Rachel Lichtenstein published the cult classic Rodinsky’s Room (Granta, with Iain Sinclair, 1999).

The Spitalfields Trust has always intended to restore the building into a public heritage site, that shares the story of the different communities who have lived in this area over time. After a long period under the management of another charity, the Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust is now leading on transforming this building once more into its latest twenty-first century reiteration. In September the Trust will start by documenting and preserving the buildings historic artefacts in collaboration with the Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archive. Further funds will need to be raised for conservation and preservation of this material.

A major capital works renovation project is in the early planning stages. The Trust will be making applications to the heritage sector and is appealing to private donors, to help it preserve and gently repair this very important historic building. Once building works are complete, the Trust intends to open it to the public with a broad programme of events and activities, which reflect the building’s history, display it powerful atmosphere and reveal its special place in the local community of Spitalfields, both past and present.

This small and beautiful historic building is unique. There are no other purpose-built synagogues still in existence in Spitalfields from this period that were established by Yiddish speaking Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who once lived in this area in large numbers. Furthermore, this is the only known example of a synagogue in the UK housed within an eighteenth-century Huguenot merchant’s house. Spitalfields is in one of Britain’s most multicultural areas, which is best known today as the home of a large Bangladeshi population. This project, including the preservation of this historic building, and the planned activities and events are of national and international significance: it celebrates the diverse history of the area, reveals the now almost entirely disappeared landscape of the former Jewish East End and the building exists as an architectural record of lost trades, communities, and former ways of life.